The Origins of the Great Wall

Nicola Di Cosmo - Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton (USA)

무지막지 간단한 요약

장성이 처음 세워질 때에는 어디까지나 중국 북방왕조에 의한 북방침략의 전진기지로서 작용하였다. 특히 과거의 최신식무기인 말의 사육을 할 수 있는 목장의 확보(지금으로 따지면 핵무기나 화학무기 제조공장밀집지대이다. 느낌이 팍팍 오지 않은가?) 오르도스로 유입되는 다양한 문화와 기술을 터득등을 목적으로 진, 조, 연은 장성을 정주민과 유목민의 분계선이 아닌 초원지역까지 끌고 올라갔다. 다시 말해서 장성의 처음 목적은 방어용이 아닌 공격용이었다.

개인적으로 놀랐다. 콜럼버스의 달걀이 바로 이런것이다. 조금 다른 각도에서 보면 이런 생각을 할 수 있구나.

반론을 하자면--

하지만 辛德勇의 해석에 의하면 由于秦昭襄王长城在关中北部地段,距离秦都咸阳较近,匈奴骑兵一旦突破秦人防线,很容易对国都造成威胁。后来汉初又沿用这道长城作为边塞。汉都长安与秦都咸阳仅渭河一水之隔,近在咫尺,二者与秦昭襄王长城的位置关系基本相当 이런 해석도 충분한 방어적인 요소가 필요했다 것의 근거가 아닐까? (수도방어의 목적)

등장하는 辛德勇의 글은 모두 张家山汉简所示汉初西北隅边境解析—附论秦昭襄王长城北端走向与九原云中两郡战略地位에서 인용한 것이다. 文史 - 关于高阙的文章

九原和云中,具有非同寻常的军事地理地位;特别是九原,不仅控制着黄河渡口,同时还控制着重要的战略通道直道,地位尤其重要。尽管在秦末丧失“河南地”以后,直道有一部分地段沦入匈奴骑兵出没之区,不能正常使用其一般的交通功能;①但若是需要采取重大军事行动,这条大通道显然依旧可以发挥无以替代的作用。因此,九原、云中两郡,各自保持单独的郡级建置,自然有利于强化治理,提升地位,以确保其能够发挥应有的战略作用。同时,让这样两个郡比肩并立,也可以令其相互牵制,更有利于朝廷的控制。(북방이민족외에 관중에서 동쪽 지역으로 군사작전을 할 경우의 작전로로서의 가능성)

장성의 정의 : 해당 시대의 주요 국가가 국방상의 이유로 장기적으로 통합적인 구조에 의하여 만들고 유지한 건축물.

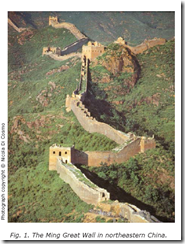

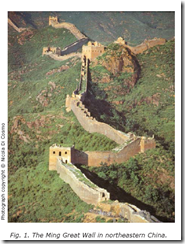

If there is a single Chinese monument that people anywhere in the world are likely to have seen, heard of, or read about, this is the Great Wall (Fig. 1). Aside from its mythical proportions, the Great Wall has symbolic powers that transcend its historical and material existence. It has been depicted as a parting line between the known and the unknown and the physical line marking the frontiers of civilization, the inhospitable liminal universe which was the preserve of a demimonde of barbarians and transfrontiersmen, convicts and soldiers, crafty merchants and banished officials. In historical writings, the Great Wall has been presented as protection against invaders — the engineering product of a superior civilization erected against the tumultuous waves of its enemies — but also

as the symbol of unrestrained, vain, and arrogant tyranny, tangible product of the blood and tears of the toiling masses. Most recently the Great Wall has acquired yet another meaning, following new orientations in the politics of historical interpretation: a meeting point of cultural exchange, compared to a river that unites rather than divides, and brings different nationalities closer together. A malleable symbol adapted to political and cultural metaphors, gate to be crossed or drawbridge to be lifted, the Great Wall of China continues to be a testimony of China’s cultural, historical, and now national identity: a most patriotic artifact.

Owen Lattimore probably was the first Western scholar to see the Great Wall more as an economic and environmental than a cultural boundary between nomads and settled people (Lattimore 1937, 1940). Arthur Waldron in his excellent study restored its historical dimension, exploding some of its myths (that it could be seen from the moon, for instance) and focusing on its construction during the Ming dynasty, in the fifteenth century, when the Great Wall became the majestic monument we can see today (Waldron 1990). Yet although the Ming Great Wall is a relatively recent creation, the concept of a Great Wall, or more correctly ‘long walls’ (chang cheng) has been in existence for a much longer time, going back to the late fourth century BCE. As astonishing as the spatial dimension of the Great Wall is, covering several thousand miles, it is its temporal aspect that has been key to its success as a symbol of patriotism and national pride, a line in the sand between barbarians and Chinese drawn even before China’s imperial unification.

Owen Lattimore probably was the first Western scholar to see the Great Wall more as an economic and environmental than a cultural boundary between nomads and settled people (Lattimore 1937, 1940). Arthur Waldron in his excellent study restored its historical dimension, exploding some of its myths (that it could be seen from the moon, for instance) and focusing on its construction during the Ming dynasty, in the fifteenth century, when the Great Wall became the majestic monument we can see today (Waldron 1990). Yet although the Ming Great Wall is a relatively recent creation, the concept of a Great Wall, or more correctly ‘long walls’ (chang cheng) has been in existence for a much longer time, going back to the late fourth century BCE. As astonishing as the spatial dimension of the Great Wall is, covering several thousand miles, it is its temporal aspect that has been key to its success as a symbol of patriotism and national pride, a line in the sand between barbarians and Chinese drawn even before China’s imperial unification.

BCE = Before Common Era : 공용시대 이전 = 기원전 (미국인 룸메이트도 몰랐던 단어라는...--)

Yet once we begin to consider the Great Wall as a historical artifact rather than as symbol, we are bound to recognize an altogether different picture. As a defense structure, its record is abysmally bad. It never prevented invasions, and it was expensive to build and maintain. The monumental futility of the Great Wall as a military installation has been demonstrated in especially stark terms during the Ming period, when massive investments did not prevent China from being attacked by the Mongols and eventually conquered by another northern people, the Manchus. China’s strategic culture seems to have favored static defense, and this may be one reason for the long existence of various types of border fortifications, and the Ming construction of the Great Wall as we know it. But was this always the case? Did the Great Wall always serve as a defensive structure? These are some of the questions I had to ask as I became interested in the early phase of the history of the frontier between China and the steppe.

만리장성을 흔히 방어적인 구조물이며, 그러한 방어적인 능력조차 떨어지는 구조물이다. 하지만 효과가 떨어지면서 수 많은 경비가 들어가는 구조물을 유지할 필요는 무엇이었을까? 우선 생각해볼 수 있는 것은 민족적인 상징으로서의 형상물이다. 그 다음으로는 장성이 방어적인 구조가 아닌 공격적인 구조를 가졌다는 생각이다.

The theory that the northern walls were erected to defend Chinese states from the nomads is well known and continues to carry much weight today. As we shall see in greater detail below, Sima Qian’s narrative account of the historical relations between China and the northern nomadic peoples in chapter 110 of his Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji, first century BCE) was based on the historical myth (an ‘invented tradition,’ some might say), according to which China and the north had been perennially at odds with one another, and that China had since the dawn of history suffered from nomadic invasions. This rationalization of what was in effect a late phenomenon, that is, the appearance of the strong unified nomadic empire of the Xiongnu, set the tone for the later Chinese understanding of relations with the north. According to this deeply rooted topos of Chinese historical thinking, which has been repeatedly asserted as recently as at the Symposium on the Great Wall held in 1994, China was weak and unable to oppose an adequate defense against the northern nomads, except for the Great Wall, which then became a symbol of resistance against all invaders (Waldron 1995). Concern for the historical ‘weakness’ of China visà-vis the nomads could not exist, of course, outside of a notion that regarded the nomads themselves as a positively aggressive, militarily superior enemy (as represented, for instance, in the Disney animated movie Mulan). As Sima Qian said, it was their innate nature to love war (Sima Qian 1993, p. 129).

Sima Qian=사마천=司马迁

Shiji = 사기 = 史记

The history of the northern frontier before the unification of China is obscure and often cast, in the earliest Chinese texts, in moralizing terms. The Chinese had already attained a high level of cultural sophistication, with music, rituals, moral norms, and especially writing. Those people who did not write, had different customs, and did not belong to the Chinese cultural and political sphere, were therefore regarded as uncivilized. Several passages can be extracted from the earliest historical documents which present the story of the relationship between Chinese and non-Chinese in terms of ‘civilized’ vs. ‘barbarians.’ Among the non- Chinese were, of course, northern peoples thought to be the ancestors of the warlike nomadic horsemen who were to become a major threat from the Han dynasty onwards. From the mid-eighth to the mid-sixth century BCE, Chinese states conducted a series of military campaigns in the north against peoples called Rong and Di. Sometimes these peoples retaliated but usually they were defeated, subjugated, incorporated, and eventually assimilated. This process was made easier by the understanding that certain rules of conduct in war (a code of honor, a sense of fair play) that were to be observed, at least theoretically, when the fighting occurred among Chinese polities, were no longer prescriptive in the case of foreign wars, where no trick or stratagem, no broken oath, no breach of loyalty carried a moral sanction or other undesired political consequences. Foreign peoples were conceived as resources, and their use as such was not only practiced by Chinese states, but also theorized.

Rong = 戎, Di = 氐

From the sparse textual evidence at our disposal we can see that the land and labor extracted from non-Chinese groups constituted a type of wealth often coveted by the Chinese states. Victories obtained against foreign peoples could serve the strategic purpose of intimidating potential enemies. Another doctrine — wrongly assumed to be pacifist — maintained that wars against foreigners had to be undertaken sparingly, because there was a risk that such ventures may weaken the state and expose it to attacks from other Chinese states. It was realpolitik, not moral values, that regulated the foreign relations between Chinese states and their neighbors. Generally

speaking, the political discourse about foreigners in pre-imperial China tends to justify expansion and conquest, which is exactly what happened. Looking closely at those statements that point to cultural differences, then, we find that such differences provide a political rationale that allowed for the expansion of Chinese polities.

Especially in the Warring States period (5th-3rd century BCE) the Chinese political and economic spaces continued to expand even though the number of independent states vying for power dwindled. The general trend was towards the creation of larger and stronger states, which expanded not only by swallowing up other Chinese states but also by expanding into external areas. If we look at the northern frontier, this trend is clearly identifiable as the states of Zhao, Yan, and Qin kept expanding and growing both militarily and economically. Setbacks occurred, but the general impulse was towards becoming stronger, and alien peoples, not integrated in

Chinese civilization, were a reservoir relatively easy to tap into. From pastoral people the Chinese imported cattle and sheep, wool, leather, horses, and pelts. Moreover, at this time the frontier economy became monetarized through the use of metals, such as gold objects possibly used as currency, and especially bronze coins. Military requirements may have played a key role, since pack animals must have been needed in increasing numbers for transportation during military campaigns as armies became larger and larger. Horses become especially important from the late fourth century BCE with the adoption of mounted warfare by Chinese states. In sum, archaeological but also textual evidence suggest a historical context, on the eve of the building of the very first ‘great wall,’ in which the northern frontier zone appears to have been increasingly valuable, in economic and strategic terms, to northern Chinese states.

Warring States period = 战国时代

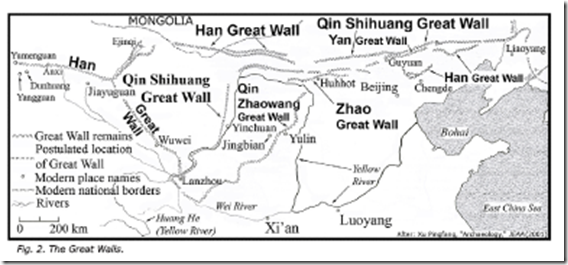

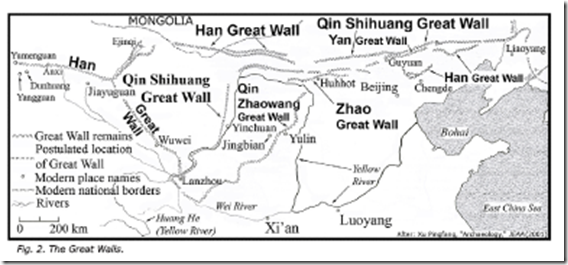

As we know, the First Emperor of Qin, the one who in 221 BCE emerged victorious from the struggle among the ‘Warring States’ and unified China, was not the one who first erected walls. He merely expanded and unified a network of fortifications which existed previously and had been established by the states of Qin in the northwest, Zhao in the north, and Yen in the northeast (see map, Fig. 2, for the various ‘walls’). Given that the conventional theory holds that the early walls were built to protect China from the nomads, historians have tried to explain why the nomads would raid, attack, or invade those lands we conventionally call ‘Chinese.’ Generally speaking, scholars have produced a number of theories more or less persuasive, and more or less supported by the sources. Some have sought to explain the nomads’ aggressiveness, for instance, with a model of omadicsedentary

relations according to which nomads need to acquire resources from their agriculturist neighbors, and would resort to war or trade to obtain them. Owen Lattimore himself saw relations across the frontier strongly determined by competing societies that differed dramatically in terms of environmental adaptation and economy. Chinese scholars have seen also in the ‘imbalance’ in the development of the productive forces on both sides of the ‘great wall’ the source of conflicts originated by the less developed side, the nomads. At any rate, all theories converge to agree that the ‘great wall’ was built as a response to nomadic aggression. To test the truth of this general apparently unshakeable belief we then should ask a most significant question: what does the evidence actually say?

Surprisingly, there is no textual evidence that allows us to establish a direct cause-effect relationship between nomadic attacks and the building of the walls. The evidence shows, on the contrary, that the building of walls does not follow nomads’ raids, but rather precedes them. If a linkage can be established in terms of mere chronological sequence, the construction of the walls should be regarded as the cause, not as the effect, of nomadic incursions. Secondly, archaeological evidence does not support the contention that the walls were protecting a sedentary population, even less that they were protecting a ‘Chinese’ sedentary population. In fact, the early walls did not mark an ecological boundary between steppe and sown, nor did they mark a boundary between a culturally Sinitic zone and an alien ‘barbarian’ region. For the most part, they were entirely within areas culturally and politically alien to China. These simple observations should already suffice to raise doubts as to the actual function of the earliest walls. More doubts are engendered as we delve deeper into the textual and archeological evidence.

1) 건축학상으로, 그리고 실제 역사적으로 증명되었다 싶이, 만리장성으로 인한 방어적 효과는 없다

2)방어적 효과를 위해서라면 만리장성 안쪽에 다수의 정주민이있어야 되었는데 오히려 적은 수의 정주민이 있다

单纯从军事防御角度看,这道新的防线足以御敌于国门之外,庇护都城的安全。但它远离关中的边防线,又带来军粮供给困难的问题。秦人和西汉朝廷解决这一地区边防军用粮共有三种办法:一是从内地调运;二是移民实边,开发当地粮食生产潜力;三是让驻军就地屯田,自食其力。

이 말을 바꾸면, 해당 지역은 농사를 하기에 힘든, 어디까지나 초원지역이었다는 소리이다. 곧 정주민과 유목민의 분계선의 역할을 했다는 말은 성립을 하기 힘들다.

《汉书》卷28下《地理志下》叙述赵国分野,谓赵国“西有太原、定襄、云中、五原、上党”,又云:“定襄、云中、五原,本戎狄地。”라는 말이 있듯이 원래는 북방유목민의 영토였다.

一是汉朝在关中不封授诸侯王国,在关中以外秦汉人习惯称之为“关东”或“山东”的东部地区,凡是沿边区域,包括实际并没有遭受多少外患,其实算不上“外接于胡、越”的渤海湾西岸地区,都被设为诸侯王封国,而频频遭受匈奴侵扰的云中郡和本文所推定的九原郡却不在其中,直接隶属于西汉朝廷.

그렇다면 매번 공격을 받는 지역을 왜 계속 지키려고 했던 것일까? 정말 방어적인 정책이었다면 이 지역을 포기하고 후퇴하는 것이 좋았을터인데 말이다. 전국-진-한에 이르도록 이 지역은 다양한 문화를 수용할 수 있고, 당시의 전략무기인 말을 사육할 수 있는 초원이 있던 지역이다. 그러므로 북방이민족은 목장을 원해서 계속 쳐들어내려오고, 반대로 중국왕조는 군사무기 공장-_;; 을 지키기 위해서 싸운 것은 아닐까?

그에대한 보충 자료로서 《管子·揆度》 桓公问管子曰:“吾闻海内玉币有七策,可得而闻乎?”管子对曰:“阴山之礝碈,一策也"와 桓公问于管子曰:“阴山之马具驾者千乘,马之平贾万也,金之平贾万也."

礝 : 古同“碝”,次于玉的美石。“碝”= 像玉的美石

어찌되었든 인산부근은 말과 보석?!이라는 두가지의 당대의 인기상품?!이 있었다. 차지할 가치가 충분히 있다.

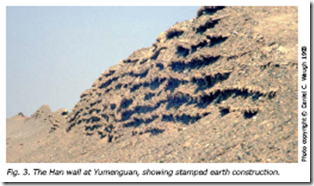

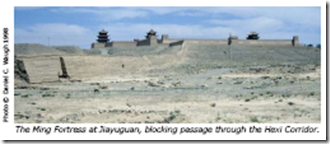

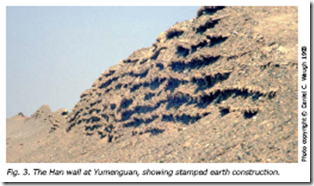

The idea and technology of such ‘long wall’ military installations is first found in central and southern China and associated with states such as Wei and Chu in the fifth century BCE. The ‘walls’ built along the northern frontier constituted an integrated system of man-made structures and natural barriers. The careful choice and use of topography enhanced greatly the effectiveness of these fortifications. This system, in addition to the ‘walls,’ included small as well as relatively large forts, beacon towers, look-out platforms, and watchtowers. Typically, the walls were made out of stamped earth and stones piled up in layers to form a rampart, usually on sloping terrain, so that the outer part wo uld be higher than the inner part (Fig. 3, next page). Moreover, along the walls archaeologists have discovered, at regular or irregular intervals, mounds of stamped earth that are probably the remains of elevated platforms or towers. On higher ground, such as hilltops or even mountain peaks, small stone structures have been found, in the shape of platforms, which are assumed to have served as look-out posts or beacon towers. On the inner side of the wall, at varying distances, we find a number of additional constructions,

uld be higher than the inner part (Fig. 3, next page). Moreover, along the walls archaeologists have discovered, at regular or irregular intervals, mounds of stamped earth that are probably the remains of elevated platforms or towers. On higher ground, such as hilltops or even mountain peaks, small stone structures have been found, in the shape of platforms, which are assumed to have served as look-out posts or beacon towers. On the inner side of the wall, at varying distances, we find a number of additional constructions,

in the shape of square or rectangular enclosures, whose walls are often made of stone, believed to be forts garrisoned by soldiers.

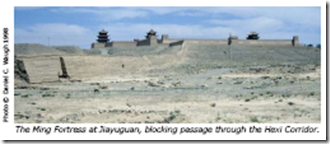

In mountainous terrain along precipices and ravines or narrow gullies, the man-made str uctures may be limited to a few towers and gates blocking a mountain pass. Roads on the inner side of these walls served the purpose of connecting the various garrisons with strategically important locations. Beacon towers, also placed on the inner side of the walls, were probably used to communicate between the various stations, although the system of communication is unclear (Fig. 4). Undoubtedly a complex system of couriers, postal stations, and checkpoints must have been operating, and the sheer number of structures and their spatial extension suggest that the efficient use of these early ‘walls’ required an extensive military presence.

uctures may be limited to a few towers and gates blocking a mountain pass. Roads on the inner side of these walls served the purpose of connecting the various garrisons with strategically important locations. Beacon towers, also placed on the inner side of the walls, were probably used to communicate between the various stations, although the system of communication is unclear (Fig. 4). Undoubtedly a complex system of couriers, postal stations, and checkpoints must have been operating, and the sheer number of structures and their spatial extension suggest that the efficient use of these early ‘walls’ required an extensive military presence.

고대의 성은 전망대(파수대)와 같은 역할을 하였다.

For instance, on top of the wall built by Qin, for its entire length, we find three to four mounds (raised platforms) per kilometer, amounting to a total of approximately 6,300 separate structures. Throughout the line of the walls, on the inner side, we encounter ruins of military installations. Citadels and forts are distributed at a distance of three to five kilometers from each other, and their internal area may vary from 3,500 m2 to 10,000 m2. They are generally walled, though forts built on steep ravines and gullies do not have walls, as the natural topography provided sufficient protection.

Turning to the evidence provided by textual sources, some caveats need to be borne in mind. The first concerns authorship, or rather the historical and cultural context from which the sources themselves originated. Explicit mention of wall building activity by the northern states is found in the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji), authored by Sima Qian around the turn of the second century BCE, that is, over two hundred years after the first northern walls were built, and after about a century of wars between the nomadic empire of the Xiongnu and China. Sima Qian inscribed such a long and bloody confrontation in a historical pattern according to which China (variously indicated as Hua, Hsia, Zhongyuan, Zhongguo, or even ‘the land of caps and sashes’) and the nomads constituted two antithetic poles that had been at odds ever since the dawn of Chinese history. Within this pattern Sima Qian produced an ethnic genealogy, culminating with the Xiongnu, that held all the various ‘northern barbarians’ together as one coherent narrative unity. As a result he created a polarization between a unified north and a unified south and projected it into the past. Sima Qian also recorded names and events whose number and variety is in itself evidence of the political and ethnic complexity of the north. Hence, while it is essential to remember that the historical narrative of the northern frontier is, not, itself, neutral, one cannot use this argument simply to dismiss all that it reveals about China’s relations with the north during the Warring States period (for details, see Di Cosmo 2002, part IV).

사기를 적은 사마천의 역사적 배경을 주의하자. 사마천은 실제 장성이 처음 세워진 때로부터 200년정도가 지난뒤의 사람이다. 그동안 흉노라는 이름으로 북방이 통일되었고, 중국도 한왕조로 통일이 되어서 장성을 두고 남북의 대립구조가 만들어 진다. 하지만 사마천이 직접 적었듯이, 고대의 중국과 북방 모두에는 다양한 민족과 국가가 존립하고 있었다.

Moving then closer to the question of the Great Wall, we need to ask whether the Shiji, as our most important historical text, supports an interpretation according to which the walls were established as a military defense. Or, to put it differently: does the historical evidence show a connection between nomadic threats and wall-building? As for the state of Qin, the record says that its king Zhaoxiang (306-251 BCE) began to build walls on the north-western border after a military campaign into that territory, which was inhabited by a non-Chinese people called the Yiqu Rong. The pretext of Qin’s expansion is attributed to a ‘scandalous’ series of events. Apparently the king of these Yiqu Rong had illicit intercourse with the Queen Dowager of Qin, who bore him two sons. Having grown displeased with the king, the Queen Dowager later deceived and killed him, assembled an army, and then proceeded to attack and destroy the Yiqu. Having conquered the Rong, Qin also expanded to the north into the territory within the Yellow River’s great bend, today’s Ordos region. In this way Qin acquired extensive new lands, which became subject to military administration, or ‘commanderies.’ Only then Qin ‘built a Long Wall to guard against the Hu.’ (Hu was a generic term to indicate nomadic steppe peoples.) The state of Yan was located in the north-east. During the reign of King Zhao (311-279 BCE), a general who had served as a hostage among the nomads made a surprise attack against the Eastern Hu. He defeated them, and forced them to retreat ‘a thousand miles.’ Yan then ‘built “long walls”’ and established commanderies ‘in order to resist the nomads.’ But this ‘resistance’ followed a military expansion well into nomadic territory. The third northern state, Zhao, also had conflicts with steppe nomads. The Shiji tells us that King Wuling ‘in the north attacked the Lin Hu and the Loufan [both of them are generally understood to be nomadic peoples – NDiC]; built long walls, and made a barrier [stretching] from Dai along the foot of the Yin Mountains to Gaoque.’ Thus, Zhao created an advanced line of fortification, deep into today’s Inner Mongolia, encircling the Ordos steppe, then inhabited by pastoral nomads. I could find only one passage that refers explicitly to a state’s need to protect itself against the nomads without this being linked to a previous Chinese expansion. This is from a debate that took place in 307 BCE at the court of the same King Wuling of Zhao during which the king strove to persuade his advisors to adopt cavalry and follow the example set by the nomads. The king said, ‘Without mounted archers how can I protect the frontier against Yan, the Hu, Qin and Han?’ In the context of the debate, however, the nomads (that is, the hu people) were not the only threat to Zhao, and throughout the whole speech it is evident that the ‘protection’ argument was accompanied by an even more pronounced expansionist argument. In any case, unlike the adoption of cavalry, the building of walls is not mentioned in connection with the protection from nomads or any other enemy.

Zhaoxiang = 秦昭襄王 or 秦昭王

Yiqu Rong = 義渠戎王

hao = 昭

King Wuling = 赵武灵王

Lin Hu and the Loufan 林胡 楼烦

Dai 代

Yin Mountains 阴山

Gaoque 高阙

与本文所论问题相关的赵国西北方边境,形成于赵武灵王“胡服骑射”之后。《史记》卷110《匈奴列传》载:“秦昭王时,义渠戎王与宣太后乱,有二子。宣太后诈而杀义渠戎王于甘泉,遂起兵伐残义渠。于是秦有陇西、北地、上郡,筑长城以据胡。而赵武灵王亦变俗胡服,习骑射,北破林胡、楼烦,筑长城,自代并阴山下,至高阙为塞,而置云中、雁门、代郡。”这道“自代并阴山下,至高阙为塞”的长城,就是赵国在其西北方的边界

특히 장성이 처음 지어질 시기, 전국시대에는 북방이민족에 대한 특별한 경계의식이 없었고, 때로는 서로 힘을 합하고, 때로는 싸우는 관계였다. 이런 관계는 "중국"이라고 불리는 내부에서도 동일하게 벌어지던 일이었다.

据《史记》卷6《秦始皇本纪》记载,始皇三十二年,“乃使将军蒙恬,发兵三十万人,北击胡,略取河南地”。翌年,蒙恬取得成功,“西北斥逐匈奴”。于是“自榆中并河以东,属之阴山,以为三十四县,城河上为塞……徙谪,实之初县。”《史记》卷110《匈奴列传》记载同一事件,云蒙恬“北击胡,悉收河南地,因河为塞,筑四十四县城临河,徙谪戍以充之”。所谓“河南地”,应当是指由秦昭襄王长城向外推延,直至黄河岸边这一广阔区域

《汉书》卷52《韩安国传》相关记载原文为:“蒙恬为秦侵胡,辟数千里,以河为竟,累石为城,树榆为塞。”

--> 어디까지나 중국 북방 왕국이 공격적이었다는 것을 증명하는 사료

This is the core evidential ground based on which scholars have argued that the northern walls had a defensive purpose, and had been erected as a protection against nomadic attacks. However, none of these statements says that walls were constructed as a result of, or as a response to, nomadic attacks on Chinese people. What they say is that the walls were built to ‘repel’ or ‘contain’ the nomads after the states had advanced deeply into their lands, had occupied their territory, and had set up military commanderies. The building of fortifications proceeded hand in hand with the acquisition of new territory, the transfer of troops to this region, and the

establishment of new administrative units. The states of Qin, Zhao and Yan needed to protect themselves from the nomads only after they had taken large portions of territory from them.

장성이 방어적 목적으로 세워진 것이라고 말하는 학자들의 발언은 어디까지나 결과론에 불과하다. 실제로 진, 조, 연이 이민족에 대한 방어가 필요해 진 것은 어느 정도 세력이 갖추어진 뒤였고, 장성은 그 전에 만들어진 것이다.

Having examined the textual evidence, let us turn briefly to the archaeological context. The material culture of non-Chinese people in what has been called the Northern Zone is fairly well known. Archaeological excavations throughout the Great Wall region, reveal the presence of a large number of bronze objects, such as knives and swords, belt plaques, horse ornaments, and precious objects. Archaeologists and art historians have long recognized this as a fully separate cultural complex which developed continuously from at least to the second millennium BCE, and usually cite among its salient features a distinctive metallurgical production and stylistic idiom, in particular the ‘animal style,’ and connections with the greater Siberian and Central Asian ‘Scythian’ art. Some of the most precious objects, usually in gold, come from the Ordos region. The remains of the Chinese walls crop up for the most part in the middle of this area, across grassland plateaus and deserts or in rough mountainous country. Chinese Warring States coins, pottery shards, and lacquered objects have been found, but the Chinese presence here at this early time was limited only to sites connected with the wall fortifications themselves, showing that military colonies and troops were stationed in an otherwise ‘barbarian’ cultural environment. For sure the walls were not built between Chinese and nomads, but ran, from a Chinese viewpoint, through a remote territory inhabited by foreign peoples. Some of these peoples were incorporated within the perimeter of the walls, some remained outside.

오르도스를 포함한 장성지역은 다양한 문화와 기술들이 서방으로부터 유입되던 지역이었다. 중국의 입장에서도 이를 받아들여야했다. 그러므로 장성은 중국과 유목민같에 세워진 것이 아니고, (중국의 관점에서는) 외국사람들의 출입을 통제하는 지역으로 사용되었다.

If we wish to understand the early function of the walls, it is on the Chinese soldiers that we should concentrate, not on the Chinese farmers. Why were the soldiers stationed so far to the north, in alien territory? The only conclusion that the evidence would support, in my view, is that the walls’ and soldiers’ presence in the northern regions is consistent with a pattern of steady territorial growth by the states of Yan, Zhao, and Qin. They developed the system of long lines of fortifications to expand into the lands of nomadic or semi-nomadic peoples, and fence them off. Soldiers defended this territory against nomadic peoples possibly expelled from their pastures. This military push created a pressure on nomads that in turn led to a pattern of hostilities. The walls, in other words, were part and parcel with an overall expansionist strategy by Chinese northern states meant to support and protect their political and economic penetration into areas thus far alien to the Chinese world. This is consistent both with the general trend of relations between Chinese states and foreign peoples and with the political, economic and military imperatives facing the Warring States in the late fourth century BCE. It was at this time that northern Chinese states began to pay attention to cavalry and to develop mounted warfare, and the local pastoral people were surely more suited to this task than the sedentary Chinese. The walls were, in other words, part of a system designed to enclose and establish exclusive access to a precious reservoir of human and material resources at a time when the bitter struggle among Chinese states had become deadlier than ever, and every state was striving to exploit any means likely to increase its chances of survival. The walls were meant as a barrier not only against dispossessed nomads but also against competing Chinese states. As such, the origins of the Great Wall are closely linked to a military and political project that will eventually result in the imperial unification of China. Recognizing the historical origins of the Great Wall does nor diminish its symbolic power, but hopefully makes it less susceptible to a purely ideological interpretation.

오히려 장성의 초기 설립목적은 전국시대 북방국가들의 확장을 위한 전진기지와 같은 역할이다. 중국 정주민은 장성을 이용해서 유목민의 목장을 침략했다. 그리고 이러한 발전으로 나중에는 통일에 이르게 된다.

About the Author

Nicola Di Cosmo is Professor of East Asian History at the Institute for Advanced Study, School of Historical Studies (Princeton, N.J.). His main interests are in the history of frontier relations between China and Inner Asia, and in the social and political history of Mongols, Manchus, and other peoples of north and Central Asia. His books include: Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History (2002); Warfare in Inner Asian History (500—1800) (ed., 2002); A Documentary History of Manchu-Mongol Relations (1616-1626) (coauthored with Dalizhabu Bao, 2003); Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries and Human Geographies in Chinese History (coedited with Don J. Wyatt, 2003); and The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China (2006).

원래 몽고어와 만주어를 배워서 박사 논문은 청대에 대한 논문이다. 그의 대부분의 논문이 기존의 것을 반대하는 주장을 펼친다. 그 근거가 되는 것은 보통 고고학자료이다. 문제는 그의 고문(중국어)능력이 비교적 높지 않은지라 논문에서 몇가지 문제가 나타난다. 이 점은 주의해서 원문을 참고할 필요가 있을듯 하다.

References

Di Cosmo 2002

Nicola Di Cosmo. Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Jagchid and Symons 1989

Sechin Jagchid and Van Jay Symons. Peace, War, and Trade Along the Great Wall: Nomadic-Chinese interaction through two millennia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Lattimore 1937

Lattimore, Owen. “Origins of the Great Wall of China: A Frontier Concept in Theory and Practice.” Geographical Review, 27/4 (1937): 529-549.

--> 구해서 보아야될듯. 장성의 유목경계설을 정면으로 부정하고 있다.

Lattimore 1940

Lattimore, Owen. Inner Asian Frontiers of China. New York: American Geographical Society, 1940.

Sima Qian 1993

Sima Qian. “Shi Ji 110: The Accout of the Xiongnu.” In: Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian Translated by Burton Watson. 2 vols. Rev. ed. New York, Columbia University Press, 1993, vol. 2, pp. 129-162. Note: the quotations above from Sima Qian are my own translations.

Waldron 1990

Waldron, Arthur. The Great Wall of China: from History to Myth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

--> 장성을 역사의 대상으로 연구를 한 책. 중요한 책. 대부분이 명장성의 정치부호와 현실중에서의 군사 그리고 그것이 현대의 신화로 변화가 된 과정을 서술하고 있다. 역사인류학계열. 예를 들어서 인민폐 내에서의 장성을 거론하면서, 예전에는 장성은 나쁜 부호였는데 근현대로 넘어오면서 좋은 부호, 심지어는 국가의 상징이 되었다.

Waldron 1995

Waldron, Arthur. “Scholarship and Patriotic Education: The Great Wall Conference 1994.” The China Quarterly, 143 (1995): 844-850.

Xu 2001

Xu Pingfang. “The Archaeology of the Great Wall of the Qin and Han Dynasties.” Journal of East Asian Archaeology, 3/1-2 (2001): 259-281.

라티모어도 장성의 기원에 대해서 논문을 작성했는데, 지리적으로 분석하면서, 농업과 유목의 분계선으로 해석하였다. 이 논문은 매우 유명한데, 장성과 농업과 유목의 분계선을 포괄적으로 이야기 했기 때문이다. 맨처음으로 중국의 농목충돌의 입장에서 장성을 이야기했다.

위의 이론대로라면 새로 해석 가능한 것들.

秦至西汉前期,匈奴是中原王朝在北方最大的边患,因此它也是秦朝重点防范的对象。이것은 흉노, 즉 유목민의 입장에서 좋은 목장(하영지)을 차지하기 위한 공격이 아니었을까?

“蒙恬死,诸侯叛秦,中国扰乱,诸秦所徙適戍边者皆复去。于是匈奴得宽,复稍度河南,与中国界于故塞。”所谓“故塞”,也就是旧时的边塞。此处所说的“故塞”,究竟是怎样的地理涵义,容下文再行详细阐述。这里首先来看一下西汉初年汉王朝在这一带的边防情况。- 辛德勇

여기서의 故塞의 해석을 다시 할 수 있다. 장성선이 아니라 그 이전에 장성을 쌓기 전에 존재했던 선일 가능성은?

秦始皇统一六国之前,秦国的北方边界是秦昭襄王时期修筑的长城。这道长城经过学者们的研究和考察,除个别地段还需要进一步深入探讨之外,其总体走势大致已经清楚,一般认为,是由今甘肃岷县附近北行,至今甘肃临洮转而向东北蜿蜒延伸,斜贯今陇东、陕北的黄土高原,直至今内蒙古准格尔旗黄河岸边的十二连城附近。①

说详史念海:《黄河中游战国及秦时诸长城遗迹的探索》,《河山集》2集,北京:三联书店, 1981年,

第453—461页。彭曦:《战国秦长城考察与研究》,西安:西北大学出版社, 1990年,第1—235页。

반론의 가능성 - 폐기-_-;;

고대에는 식목의 북방한계선이 훨씬 높았다. 다시 말해서 해당 지역은 목장이 아닌 농장가능지역이었을 점에 대한 고증을 해볼 필요가 있다. ---》 이는 해당지역에 농사를 짓는 사람이 없었다는 것으로 반론할 수 있으므로 통과

성 자체는 긴 구덩이(참호?!)가 발전된 형태이고, 초기의 형태는 홍수를 방어 혹은 동물의 침입을 막기 위한 것이 아닌가 생각된다. 반포유적의 경우 참호로 보호되어있다. ....